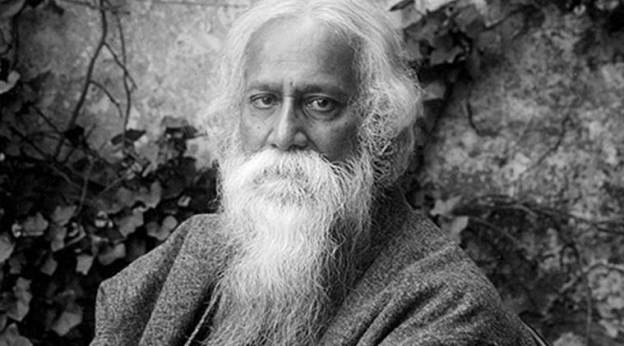

May 7th is the 164th birthday of Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), the Bengali poet and Nobel Prize winner of Literature in 1913. Tagore’s ability to live a rich and fully creative life remains an inspiration. Poet, author of novels and short stories, lecturer, essayist, playwriter, song writer, founder of three educational institutions, and – during the last ten years of his life – painter, Tagore’s creative approach to being in the world provides us with a model of what it means to be fully human and in relationship to everything around us.

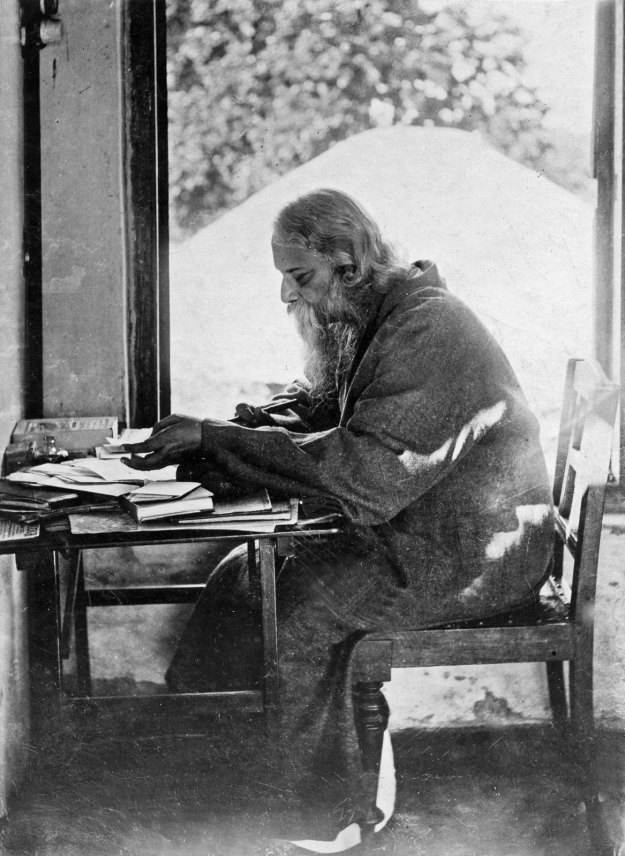

Roberto Assagioli met Tagore in the late spring of 1926 during Tagore’s third visit to Italy. Upon their meeting in Rome, we can easily imagine the younger Italian psychiatrist’s enthusiasm for the great Bengali poet and musician. Besides being world-famous, Tagore was Assagioli’s senior by twenty-seven years, possibly evoking feelings in the latter of meeting a spiritual father.

To celebrate today, here are five fun facts about Tagore and psychosynthesis.

1. Tagore as an Ideal Model

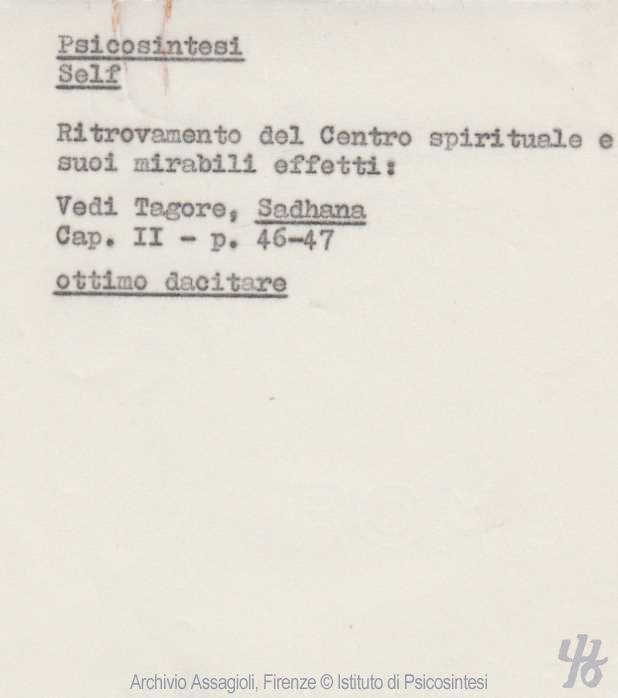

Assagioli referred to Tagore as an example of someone who has completed the process of psychosynthesis and notes that Dante’s Divine Comedy and Tagore’s writings are both testimonies of superconscious exploration. Assagioli also suggested Tagore might act as an ‘Ideal Model’ for persons seeking psychosynthesis.

Assagioli was not alone in recognizing Tagore’s wholeness as a human being. Throughout Tagore’s lifetime, many people referred to him with the appellation of ‘Gurdeva’, meaning ‘revered teacher’, a title bestowed upon him by Gandhi. Sisir Kumar Ghose (1840-1911) described Tagore as a “complete man,” and writer and poet Richard Church (1893-1972) entitled his essay about Tagore “The Universal Man”, in which he described Tagore as “an example of a harmonious man… guided from the beginning by a direct and unquestioning vision which led him toward a philosophy of wholeness, of unity.”

2. Tagore Balanced and Synthesized Polarities

Balancing polar energies is essential to psychosynthesis. Tagore clearly recognized the opposition of forces in all of creation and even in his own poetry, writing, “If the divergence is too wide, or the unison too close, there is … no room for poetry. Where the pain of discord strives to attain and express its resolution into harmony, then does poetry break forth into music.” Tagore demonstrated unity in opposites not only in his poetry but also in other areas of his life. For example, his desire to create Visva-Bharati University could be seen as a place where the opposite poles of Eastern and Western thought, culture, and religion could converge, harmonize, and synthesize into a higher level of spiritual unity.

3. Tagore Wrote About His Subpersonalities

One could say that Tagore’s authentic ‘I’ – the times when he felt most free, joyful and himself – was when he was writing poetry. However, Tagore often felt inwardly torn between himself as a poet and his conflicting subpersonalities (although he did not name them as such). In 1921 Tagore wrote: “Sometimes it amuses me to see the struggle for supremacy that is going on between the different persons within me.”

Throughout his lifetime, Tagore would struggle to integrate and ultimately synthesize his numerous subpersonalities into an authentic whole. In his letters to Charles Freer Andrews, Tagore often described the Poet within him in conflict with such inner persons as: The Preacher, Politician, Patriot, Teacher, Leader, the man who is Good, and the Prophet. In one letter he described a number of these subpersonalities having a conversation.

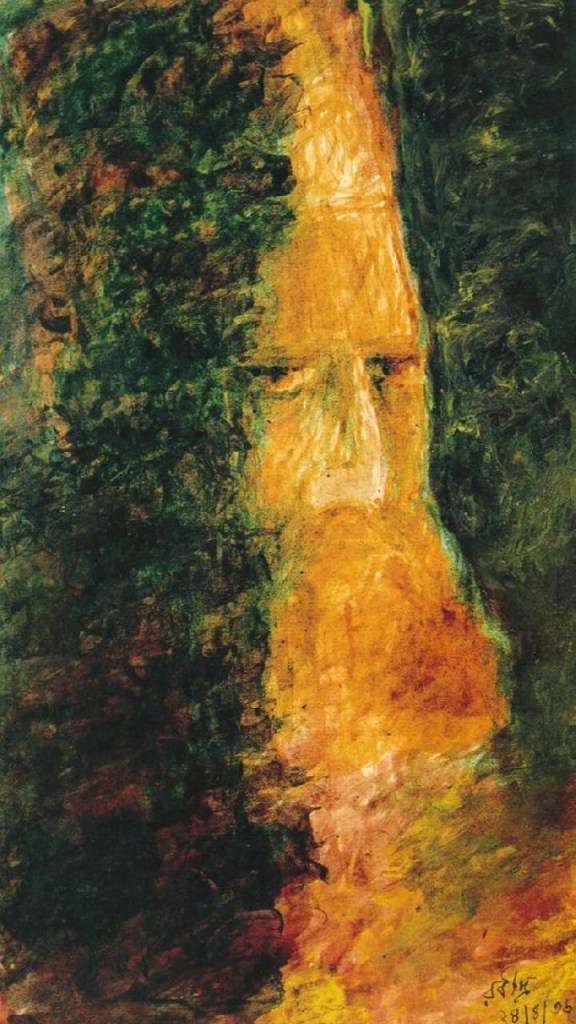

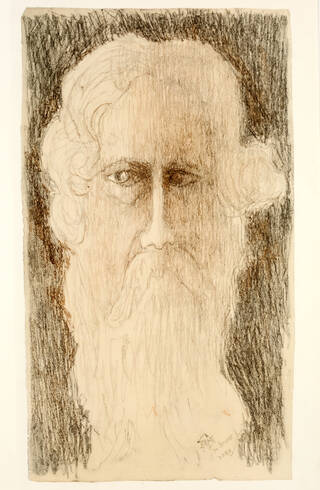

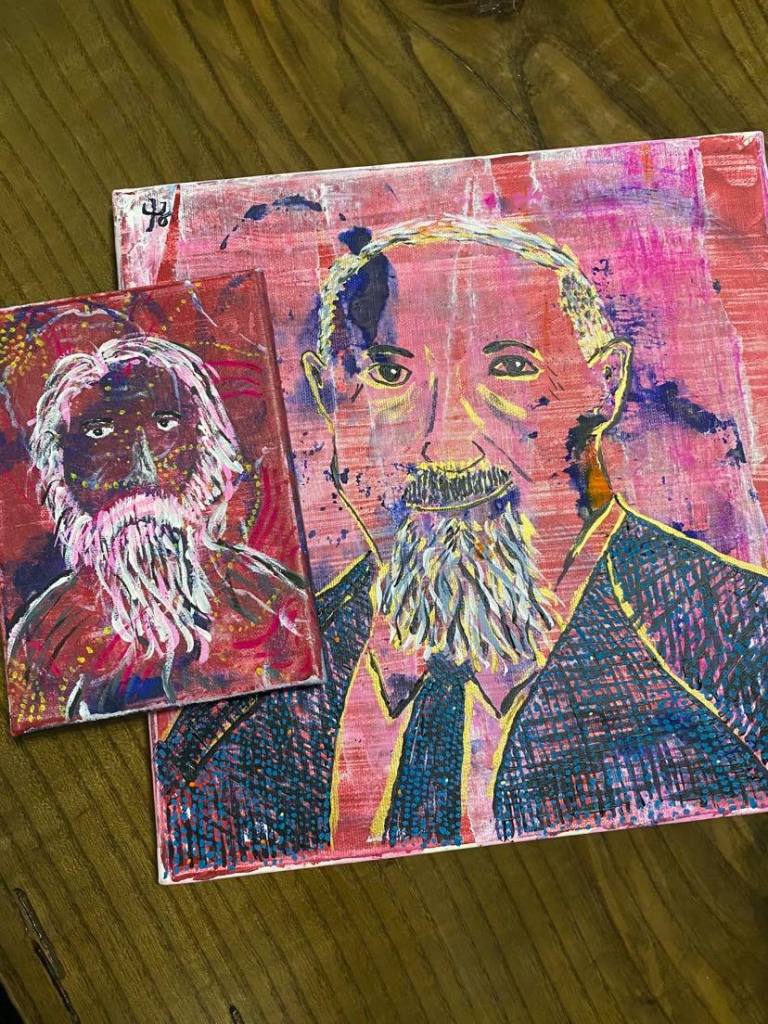

At the end of his life, Tagore produced ten to twelve self-portraits as ink drawings or paintings, all of which reflected his inner self. Each self-portrait is uniquely different from the others, perhaps an expression of his subpersonalities. Tagore painted or drew his facial expressions to show everything from anxiety to apprehension, from wonder to feelings of pain, sorrow, grief and ridicule towards power.

4. Tagore Described His Transpersonal Experiences

Tagore described moments when he was able to touch the Infinite and become intensely conscious of it through the illumination of joy. While Tagore did not specifically name such incidences as ‘transpersonal experiences’, he described them as “a sudden spiritual outburst from within me, which was like the underground current of a perennial stream, unexpectedly welling up on the surface.” In his book The Religion of Man, he also recognized the “realization of transcendental consciousness accompanied by a perfect sense of bliss… carrying in it the positive evidence which cannot be denied by any negative argument of refutation.” He then asserted that, while not a religion per se, such a union of one’s being with the Infinite was “valuable as a great psychological experience” (my emphasis).

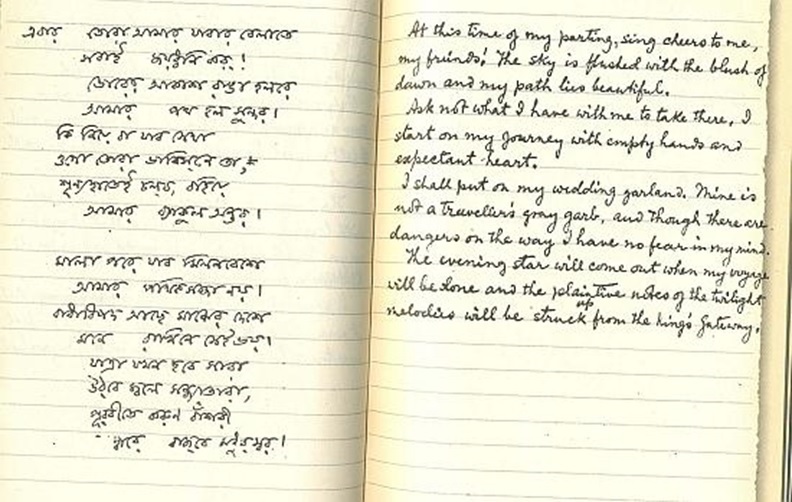

One of Tagore’s earliest transpersonal experiences occurred when he was a primary school student struggling with his spelling lessons. He described how the writing appeared to him as “irrelevant marks, smudges and gaps, wearisome in its moth-eaten meaninglessness.” But then he came upon a rhymed sentence, roughly translated into English as ‘It rains, the leaves tremble’. Upon reading this sentence, Tagore was suddenly transported beyond the classroom:

“The unmeaning fragments lost their individual isolation and my mind revelled in the unity of a vision… I felt sure that some Being who comprehended me and my world was seeking his best expression in all my experiences, uniting them into an ever-widening individuality which is a spiritual work of art.”

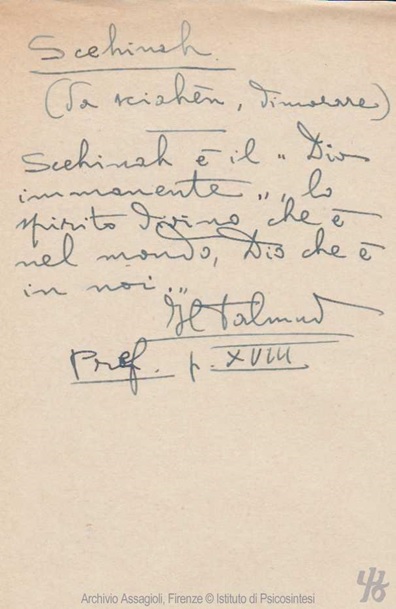

5. Tagore and Assagioli had Similar Spiritual Philosophies

Although Tagore and Assagioli came from different cultural and linguistic inheritances, both of their spiritual philosophies underwent a similar evolutionary process. In particular, they shared a vision of how the Infinite is expressed through the finite individual. What is perhaps most striking when comparing both men’s philosophies is that, despite their unique experiences and diverse cultural heritages and backgrounds, each managed to integrate his experiences with his knowledge of various cultural sources and spiritual traditions to synthesize a visionary understanding of the transcendental personality of humankind.

You can read more about their shared spiritual philosophy in my published article: “The Eternal Stranger Calls”: The Spiritual Philosophies of Rabindranath Tagore and Roberto Assagioli” published in the Journal of Indian Philosophy and Religion.

Conclusion

As far as we know, Tagore was not familiar with psychosynthesis psychology, however, many of his visionary ideals and life experiences as expressed in his literary works, songs, and paintings easily correspond to many of its concepts. Undoubtedly, Tagore does provide us with an excellent example of someone who has accomplished the long process of psychosynthesis, both personal and spiritual.

Happy Birthday Rabindranath Tagore!

Many thanks to Ruchira Chakravarty for encouraging me to write this blog.