Today is Roberto Assagioli’s 136th birthday. So I thought this might be a good time to explore what we know about his time in Russia and his relationship with a Ukrainian couple whom he knew in Rome.

Assagioli’s Trip to Russia in 1911

We have Assagioli’s own account of his visit to Russia in 1911.[i] At that time, Russia was a constitutional monarchy and in great political turmoil. Assagioli tells how during his time in Moscow, he managed to engage both with the aristocrats associated with the Italian embassy and revolutionary students. He said:

“I saw it was very evident that the whole regime was corrupt and impossible, and on the verge of cracking.”

Learning Russian and Understanding the Russian Psyche

But let’s start at the beginning… In his autobiography, he talks about helping Vera Mitrofanovna Bogrova (c. 1890-?) obtain an illegal Italian passport. She was a social revolutionary (as opposed to a ‘communist’) who had been released from Russian prison and had escaped to Florence. She was chief of the Russian organization of revolutionary medical students.

Needing to finish her medical degree, she enrolled in the university in Florence. That’s where Roberto and Vera met and became good friends. Assagioli and Madame Bogrova would sit together in the back of anatomy classes so he could practice speaking Russian. He also recounts that she introduced him to Slavic psychology. (In a note from his archives, Assagioli suggests reading Edgar Wallace’s novel The Book of All Power in order to understand Russian psychology.)

But Bogrova found Florentine life boring and longed to return to Russia to join her husband and continue her work in the revolution. Assagioli thought she was a bit crazy to return, but then helped her obtain the passport. “You go there,” he said, “and if you’re not caught, I’ll come to Russia.”

Bogrova did return to Moscow under the guise of being Italian and managed to evade detection. She was soon able to reunite with her husband, posing as his Italian lover! So that summer, Assagioli traveled to Moscow. He was friends with the Italian writer Dora Melegari (1849-1924) who was the sister of the Italian ambassador

(1854-1935). Hence, his access to the ambassador who was located in St. Petersburg.

Just a brief tangent to say the Dora Melegari played a leading role in the founding of the National Council of Italian Women (CNDI) in 1903 and in its First National Congress in 1908. This is the same organization founded by Contessa Gabriella Spalletti Rasponi (1853-1931) who was the first President of the Institution of Psychosynthesis.

Helping a Damsel in Distress

Okay, now back to Moscow. While there, Assagioli introduced himself as a medical student and attended the first Meeting of the Russian Union of Psychiatrists and Neuropathologists. He also attended a lecture by Nikolai Onufrievich Lossky (1870–1965), a Russian philosopher who promoted evolutionary metaphysics of reincarnation.

One September morning, Bogrova entered her friend’s apartment where Assagioli was staying and said, “Hurry up! Get up! My cousin has murdered the Prime Minister.” The assassin was actually her brother-in-law Dmitrii Bogrov (1887-1911). He had killed Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (1862-1911) during an opera theatre performance in Kiev in the presence of the tsar and his eldest daughters.

Mystery Murder

No one is certain to this day why Bogrov (above right) killed Stolypin (above left). Assagioli also discusses the possible reasons. Some say Bogrov was influenced by conservative monarchists who were opposed to Stolypin’s reforms and his influence on the tsar. Others say Bogrov was a revolutionary planted inside Stolypin’s circle of secret police in order to kill him. There is the theory that the police wanted Stolypin dead because he was trying to clean up police corruption. Another theory is that Bogrov was being pressured by the revolutionaries to kill Stolypin in order to prove his alliance to them. Still others say that, as a Jew, Bogrov was taking revenge for the recent Russian pogroms. Who knows what combination of reasons he might have had?

Cover of the Neurology Bulletin 1911.

In any case, Assagioli once again came to the rescue of Madame Bogrova. Being a relative of the assassin, she was afraid of being arrested. At one point, Assagioli accompanied her to the Italian Consul in Moscow, telling her not to speak of word of Italian, for her accent would give her true nationality away. By this time it was October, and Assagioli soon took a train back to Florence. Bogrova disappeared. He never saw her again.

More to Investigate!

If anyone lives near Columbia University, you might consider making an appointment to visit the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. There you can view the Vera Mitrofanovna Bogrova Papers. Included are her manuscript memoirs (in Russian), which deal with such topics as her childhood, the Bogrov family, the Russian revolutionary movement, and the “Jewish Question” in Russia (she was Jewish). There are also three documents relating to Grigoii Girgor’evich Bogrov, Bogrova’s father-in-law and the father of the assassin Dimitrii Bogrov.

Who knows if she mentions Assagioli and can collaborate his story?

Assagioli’s Stay with Nina Onatsky, Ukrainian Nationalist

Now let’s jump ahead thirty years to 1940. Once released from Regina Coeli prison, Assagioli wrote in Freedom in Jail that he gave up his apartment in Rome and found a “friendly refuge: N.O.’s pension”. We now know that N.O. was Nina Onatsky. But who was she? I spent a day on the internet trying to find out, and I virtually ended up in the Elmer L. Andersen Library at the University of Minnesota.

Ukrainian delegation at the International Women’s Congress in Rome in 1923. Nina Onatsky is on the right.

Nina was the wife of Evhen Onatsky (1984-1979), an Ukrainian, who at the time of Assagioli’s release was teaching Ukrainian language at the University of Rome. Nina was “a very noble and refined lady,” university graduate and ran the pensione in order to raise money for her husband’s publications.[2]

Who was Evhen Onatsky?

In 1943, E. Onatsky was also thrown into Regina Coeli prison! And so the plot thickens…

Evhen Onatsky

Political activist, historian, journalist and diplomat, Onatsky played a major role during the Russian Revolution in 1917, which earned him a high ranking post in Ukrainian politics. He came to Italy in 1920 as chief of the Ukrainian Press Bureau. Only 26 years old, he was fluent in Italian when he arrived. But then in 1923, the government of Ukraine was overthrown by the Russian communist regime. At that point, Onatzky became a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), an international political organization that believed in violently overthrowing Soviet Russia for Ukrainian independence.

At the start of WWII, Onatsky and the OUN was pro-German, hoping that the Germans would help the Ukrainians defeat Russian rule. About the time he must have known Assagioli, Onatsky was writing pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic material (under a pseudonym) for the Germans. He was also secretly acting as a political advisor for the head of the OUN, who the Germans persecuted. Onatsky then secretly became the new OUN leader.

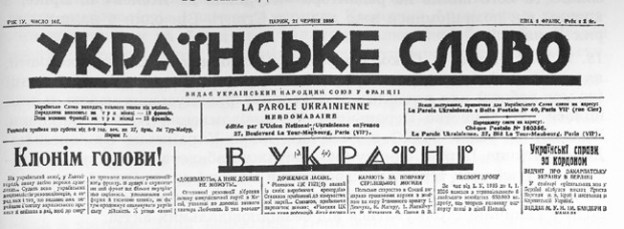

La Parole ukrainienne (Ukrainian Word), a weekly newspaper closely allied with the OUN. It serves as an unofficial organ of the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists. As a prominent figure, Evhen Onatsky often wrote for this newspaper.

Once Onatsky realized that the Germans had no intention of returning Ukraine to the Ukrainians, he switched sides and that’s when the Germans jailed him, later sending him off to Berlin and Oranienburg prison camps.

In 1945, Onatsky was freed from jail and returned to Rome. Supported by the Americans of Ukrainian descent, he took charge of the Ukrainian-American Relief Committee in Italy. After two years, he and Nina migrated to Argentina where they lived out their years in Buenos Aires. Among the Ukrainian community, Onatsky become a well-known Ukrainian scholar and folklorist.

But the story doesn’t end there! It’s amazing what you can find on the Internet… While in Argentina, he was investigated by the CIA for his anti-communist activities. You can read his declassified CIA file here.

Meanwhile, if you live near the University of Minnesota, you might like to visit the Elmer L. Andersen Library and look through its Evhen Onatsky collection. They have 46 boxes of material including correspondence with Benito Mussolini.

Note from Assagioli’s Archives: “Non esistono problemi!” (Problems don’t exists!) / Nina Onatsky

So we can see from both stories, that in war, there are often no clear cut sides. People have all kinds of agendas, alliances, and wills of their own. (Tolstoy writes about this brilliantly in War and Peace.) Life is complex and the people and their desires even more so.

Happy Birthday Roberto!

[i] See Roberto Assagioli, Roberto Assagioli in his own words, Fragments of an autobiography (recorded by E. Smith – edited by G. Dattilo, P. Ferrucci, V. Reid Ferrucci), Firenze 2019, Istituto di Psicosintesi, pp. 38-44.

[ii]. Autobiography of Anthony Hlynka (trans.), printed in Oleh W. Gerus and Denis Hlynka, ed., The Honourable Member for Vegreville: The Memoirs and Diary of Anthony Hlynka, MP, Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2005, pp. 127-128.