Joy.

For a year now, I have been a volunteer working one morning a week for the local Italian Catholic organization Caritas, which means ‘charity’ in Italian. This national organization, funded in part by the Vatican and in part by donations, offers food and clothing to the poor, subsidizes housing, pays medical bills, and tries to find or create jobs for the unemployed. During this past year, I have done everything from teach asylum seekers English, pack and distribute groceries for the needy, canvas for food outside supermarkets, help run an auction, perform basic office work, and hang out with people in the Caritas waiting room.

One sweltering July morning, Rose (Note that all names have been changed) showed up hot and sweaty and on the verge of tears. She had walked three miles in the sweltering heat pushing her 4-month-old baby girl in a rickety stroller down a road full of racing Italian traffic and no sidewalk. Rose plopped down onto a chair and started sobbing. Everything was just too much. Despite having been in the country for two years, she still didn’t understand much Italian. (I would realize months later that she could barely read and write.) That day she sat gripping another official letter that can had come in the post. One of those bureaucratic letters full of convoluted language that just tells you to wait for another bureaucratic letter to arrive someday soon.

Rose speaks English, so we were able to easily communicate. The first thing I did was offer her a drink of water. The first thing she did was hand me a raggedy little book about the size of your palm. Inside, on a few stapled sheets of paper, were the notes Italian immigration officials had scribbled upon her arrival in Sicily. Female. 27 years old. Picked up at sea. Post traumatic stress. Nigerian.

Immigrants arrive off the coast of Sicily.

And so our journey together started. I entered her world of being poor, black, African and unwanted as we tried to maneuver our way through the Italian refugee system. This included trips to the city hall, the hospital, the welfare office, the post office, the baby’s doctor, the center for the baby’s vaccinations, the county office for asylum seekers, and police headquarters. We went and stood in lines, not just once, but at least three or four times before securing the needed stamp, document, signature, seal of approval, or digitalized card.

Soon after we met, she and the baby were evicted from their apartment. This meant a frantic search for another apartment, more documents, more signatures, meetings with less than helpful and not very friendly realtors, and final moving arrangements. Caritas was continually supportive, undersigning her rental contract, paying an unemployed man to help her move, and arranging for a needed plumber. Since 2017 the Catholic church in Italy has taken in 25,000 migrants, financed in part by EU funds. More than 2700 asylum seekers have been assisted with Vatican money alone. At one point, the director of Caritas pulled me aside and said, “Caterina, we wouldn’t be doing any of this without you involved. You don’t just put somebody in an apartment and say arrivederci. You become a part of their life.” And so this entire adventure seemed to sneak up on me. I was suddenly learning what it really meant to help somebody. Naturally, my husband Kees became a part of this story too, and we are now committed to helping this little family as best we can.

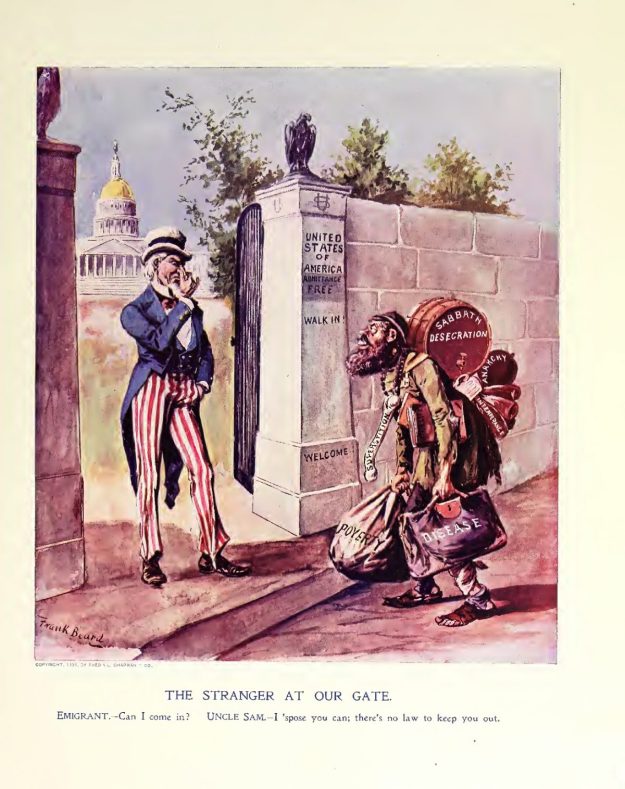

“The Stranger at Our Gate” by Frank Beard (1896). Has much changed in more than 100 years? Even the wall is there…

In between all this running around with Rose, I would insist that we take a break, sit down in the shade and have an ice cream. Joy would hungrily suckle and Rose would hungrily devour her frozen yogurt. I greedily gulped down the fortifying and much needed café macchiato. More than once in the middle of the café or gelateria, Rose has dropped down on her knees to thank me for all that I have done. Since her arrival in Italy, I am the first person who has ever been nice to her. I am embarrassed by her display of gratitude as well as a bit frightened by its intensity. “Please get up!” I plea as I tug at her sleeve. “There’s no need for that. You are more than welcome.” From the start, she has called me ‘Mama’ and Kees ‘Daddy’, but I’m pretty sure those are names given to elders in her home country. In any case, as her surrogate mother, I have spent time fretting, worrying and praying for her.

Now, you might be wondering about Joy’s father. His name is Samuel (32) and he too is from Nigeria. When I first met Rose, he was picking tomatoes and lettuce in the fields in Sicily, a 24-hour bus ride from where we live. Earning €35 euros a day, he slept in the bush and sent most of the money to Rose. But that job ended and now he is here, looking for work as a brick layer and house painter, which is his profession. He too speaks little Italian, even after being in Italy for four years. His search for work is nearly hopeless especially where we live, as most young Italians in our economically depressed area have to leave to find work elsewhere. So Samuel travels by train to a nearby town to beg. Whenever I ask Rose where Samuel is, she says he’s doing “Buon giorno. (Good morning.)” That means he’s off begging, probably at the supermarket where the local police look the other way while refugees ask to return your shopping cart for €1.

Immigrant Children at Ellis Island (1908).

Rose and Samuel already knew each other back home. But Samuel had to flee Nigeria because gang members raped him and then threatened to turn him into the police if he didn’t join their gang. Homosexuality is a criminal offence in Nigeria. Rose followed him two years later with her sister, who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. Once Rose arrived in Sicily, she ran away from the Italian refugee program she was in because they refused to tell her where her sister was buried and they wanted to send her to Napoli. When I asked her why she didn’t want to go to Napoli, Rose just shook her head. “Napoli and Africa. They’re the same thing.”

In fact, nearly 80% of Nigerian women who come to Italy are forced into prostitution by the Italian or Nigerian mafia. I kept thinking that at least I can try to save Rose from such a horror.

This whole immigration thing is a mess. Boatloads of people drowning every week in a sea where we love to swim and spend our summer holidays. The West and now China robbing the African continent of its minerals for our smartphones and its petroleum for our cars. Italy’s Interior Minister Matteo Salvini closes – without notice – a refugee center near Rome that houses 500 men, women, and children, many enrolled in local schools. “I did what any good father would do,” he said. The money saved will be spent on “helping Italians.” Does it make any sense?

You can debate whether Rose and Samuel and Joy should be here at all. But that’s not the point. The point is they are here. I once asked them about their journey from home – across Nigeria, Niger, Libya, and the sea. They said that the drive through the sub-Sahara desert was “sheer terror.” “You got nothing to eat or drink, and if you got sick, they just tossed you out of the truck to die alone like a dog.”

Encountering the many government officials with Rose, I have experienced the icy brutality of racism and the callous indifference to the poor. Caught in the middle as her translator, I have seen officials refuse to help her, or worse, lie right in her face. Not everyone is unkind. As we wait in the welfare office for our appointment, Joy is swept away by a battalion of cooing Italian women and passed from one admirer to another. Everyone wants to hold Joy. Her eyes seem to reflect deep, ancient pools and her solid limbs seem rooted to a forgotten Mother Earth. She never seems to cry. In Nigeria, Rose was a hairdresser, a braider of African hair, so Joy’s hair is always woven into an elaborate work of art that you cannot help but notice. Everyone loves Joy. But, quite frankly, nobody wants her mother or father.

I have learned how it’s best to start every conversation I have with an Italian bureaucrat with wide innocent eyes (a long-time specialty of mine). “I’m terribly sorry,” I speak slowly in thickly accented Italian. “I’m American (this is obvious) and I work as a volunteer for Caritas. Please forgive me. I am completely ignorant of how these things work.” This confession softens the uniformed official in front of me, instantly turning him or her into the expert in control, as I become the helpless little americana. The truth is I am completely ignorant. After all I’ve never had to ask in my own country, in my own language – never mind in Italy in Italian, for visa documents or social assistance or food money or health care subsidies.

Choices. Rose and Samuel and all of us have made our own choices. Choices that reverberate over time. Choices that made sense when we made them and make no sense now. Choices that felt as if someone else made them for us. God’s choices. Choices that were a lucky guess.

“Internazionale dello Spirito. (Internationalization of the Spirit)” (Note from Assagioli’s Archives)

Samuel is Catholic and Rose was raised as a Jehovah Witness. With the hope of helping them to integrate, we have gone with them to Sunday mass in the town’s cathedral. Samuel would like Joy to be baptized. But then, while making the baby’s arrangements, we discovered that Rose has never been baptized. So on Easter, mother and daughter will be baptized together and Kees and I will become double godparents.

To prepare Rose for this sacrament, the priest Don Emmanuele comes once a week to their home to give an hour’s worth of Bible study. Don Emmanuele is from Togo, a tiny West African country and former French colony. He gives the lesson in Italian and Kees translates it into English. Don Emmanuele has lived in Italy for the past 10 years. Handsome with beautifully proportioned features and milky brown skin, his sad, tired eyes light up whenever he starts teaching us about the Bible. We are working our way through the Old Testament. Lots of stories about women not being able to get pregnant and threatening to kill themselves and brothers killing or trying to kill each other. “No matter what difficulty you find yourself in, no matter how hopeless your life seems,” Don Emmanuele concludes at the end of the hour together, “turn to God. Pray to God. Because God always has a plan. It might not be realized right away. But if you are faithful to God, good will prevail.”

Samuel’s final plea for asylum in Italy is in April. His lawyer says he would have a better chance in court if Rose and he were legally married. To get married, the first thing they both need are official documents stating they are Nigerian. This means they have go to the Nigerian Embassy in Rome. One of the Caritas lawyers has said the Nigerian Embassy is the most corrupt in Rome. And that’s saying a lot. The embassy wants €200 from each of them for a piece of paper. If we throw Joy in (her papers now say she is “stateless”) that’s a total of €600.

€600 is a lot of “buon giornos”. It’s a lot of shopping carts to collect in the dead of winter.

Rose, Samuel and Joy. Will you help? I’m shooting for a clean €1000 to cover documents, trips to Rome, all the Italian bureaucratic expenses, a dress, a cake. I promise whatever is left over will go to the local Caritas.

Can’t you see? I’m doing a “Buon giorno”.

Grazie and God Bless You.

To help, please use our Paypal account purshana(at)live(dot)com or contact me for bank details.

Assagioli’s note from his archives.

Psicosintesi Internaz. – Comprensione / Psychosynthesis Internationaliz. – Understanding

Apprezzamento / Apprecation

Necessità di mutua integrazione (scambio) / Necessity of mutual integration (exchange)

Cooperazione ai varii livelli / Cooperation at the various levels

Gruppi di Nazioni / Group of Nations

Continentali / Continentals

Per affinità / By affinity

Fra continenti / Between continents

Oriente occidente / East West

Europa Africa / Europe Africa

ecc. / etc.

Ψς d. Umanità / Psychosynthesis of Humanity

Nuova civiltà mondiale / New world civilization

Nuova cultura mondiale / New world culture

Sintesi organica (non conformità) / Organic synthesis (non-conformity)

Moving and beautifully written. It helps understand that immigration issue in a more human light. Thank you.

Thank you for all you do Catherine. What a deserving couple! I would like to donate. Can I do so in dollars?

Yes, of course. Thank you for your loving support.

Hi Catherine,

I remember that you told me part of Rose’s story during the walk we made with our dogs here in Leivi last autumn.

I am glad that I can make a contribution so that hopefully, by the help of many, the young family can settle down in Italy.

Please let me know the bank account for the money transfer.

Lots of love to you all!

Sabine

Hi Catherine, I would love to donate. Please let me know the bank info or zelle act (anything) to send our donation to. xoxo Karen