This is the third and last part of a series that explores psychosynthesis and Jungian analysis based on my article Psychosynthesis and Jung in a Nutshell.

In Part I I summarized some of the differences and similarities between Jungian psychology and psychosynthesis.

In Part II, I reflected on the relationship between these two great geniuses.

In this part, I will offer some of my own reflections on Jung’s concepts, which are confirmed by Assagioli.

Jung’s Writings Lack Clarity

Firstly and perhaps most importantly, one statement that seemed to be consistent throughout Assagioli’s notes, which resonates with my own opinion, was Jung’s writings lack clarity. I have often felt that Jung’s language is muddled and his writing verbose and meandering as opposed to Assagioli’s carefully crafted and meticulously worded books. Perhaps this is exemplified by the number of books attributed to both men. While Assagioli published five books (two posthumously), The Collected Works of C. G. Jung is a book series containing 20 volumes!

Edward C. Whitmont (1912-1998), a Jungian psychoanalyst who introduced many Americans to the fundamentals of Jungian psychology, once said:

I must warn you that insight into or comprehension of what Jung really stands for can not be gained from his published writings. Quite frequently they hide more than they express, unless, of course, you can read between the lines… I want to emphasize that you cannot judge what Jung said from his writings; you can judge [analytical psychology] only from the way it is being practiced.

Explaining that the only way to really understand Jung is through personal experience, Whitmont then related an example from when he was Jung’s student. Perplexed by a concept that Jung had written about, he asked Jung to further explain it.

“Where the hell did you read this nonsense?” Jung asked him.

“In your book!” Whitmont responded along with the page number and paragraph.

“Oh forget it!” said Jung.

If Jung tells his own students to forget about his writings because they contradict what he wants to express, and his own student warns us to not expect to understand Jung from his writings, then what are we supposed to understand from his publications?

The Animus Does Not Correspond to the Female Reality

Secondly, I have never been comfortable with Jung’s concept of the “animus” for women as a counterpart to the male principal of the “anima.” Jung used these terms to define: “the inner figure of a women held by a man and the figure of a man at work in a woman’s psyche.” The anima is a personification of all the feminine psychological tendencies in the male psyche. As a rule, the anima is shaped by the man’s mother and can manifest as and/or be projected upon both negative and positive symbolic figures.

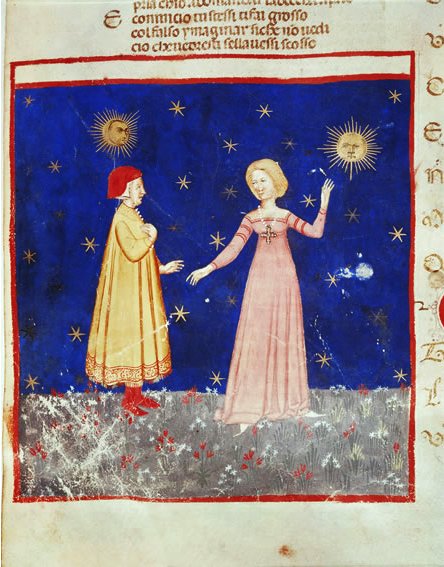

The anima also personifies man’s relation to his unconscious. Negative figures include the femme fatale, the Greek Sirens, witches, and women who appear in erotic fantasy. Positive figures include romantic, idealized beauty, like Helen of Troy. Higher positive images include spiritual wisdom like the Chinese goddess Kwan-Yin who can bestow the gift of poetry or music and even immortality on her favorites, Sappho or the Virgin Mary.

Most importantly, however, according to Marie-Louise von Franz, the anima has the essential role of “conveying the vital messages of the Self” and “putting a man’s mind in tune with the right inner values and thereby opening the way into more profound inner depths.” Examples of this anima role appears in literary works such as Dante’s Divine Comedy in the form of Beatrice and as “the eternal feminine” in Goethe’s Faust.

The Impoverished Animus

In contrast, the male personification of the unconscious in women – the animus – does not play such a vital role for the female psyche. For example, while Dante’s spiritual journey may be the complete poetic form of psychosynthesis, his search for Beatrice is, nevertheless, quintessentially male. Dorothy L. Sayers argues that while Dante’s journey to Beatrice could symbolize man’s search for his anima, for the female “from time immemorial…there is no corresponding Enigma of Man.” She continues by pointing out that, in fact, Jung’s:

… corresponding animus in the female [when compared to] the rich, poetic, and magical content of the animain the male [is] so desiccated, impoverished, and lacking in any touch of the numinous that it might appear to have been artificially patched together for the sole purpose of completing the symmetrical pattern.

I am in total agreement with Sayers. I have always viewed and experienced the animus as the part of a woman’s inner psyche that seems to know how best to manage the patriarchal world in which she must cope and survive while being judged and treated (for the most part) as an inferior being. In a world that has been dominated by men for thousands of years, if anything, the animus is usually over-emphasized in a Western woman’s conscious life, especially when she is pursuing a successful career.

Instead of an Animus, A Triple Goddess

Similar to the anima, the animus can also manifest as and/or be projected upon both negative and positive symbolic figures. However, I do not believe that the animus personifies a woman’s relation to her unconscious nor is it the animus that can open the way to her inner depths or values. This door is unlocked instead by the triple power of the inner Divine Mother, the Dark Sister, and the Crone.

As Jungian Silvia Brinton Perera states, before grounding myself as a woman in order to “coagulate [my] feminine potency to confront the patriarchy and the masculine as an equal,” I must first come into relation – not with my male psyche tendencies – but rather with the ancient parts of my repressed feminine self. These parts of me are “too awesome to behold, the Great Round of nature, connected to active destruction but also to transformation.”

I was elated to have my intuition and feelings confirmed by this note by Assagioli:

Polarity and struggle between the artificial “personality” constructed for society and the unconscious repressed elements, regrouped by Jung under the designation of “anima” (questionable as a name and questionable as a unified grouping – in reality these elements remain multiple and often contrasting. Also this conception would only apply to men, not for women.)

Once again Assagioli first questions Jung’s choice of the term “anima” (which is Latin for ‘soul’). He then continues by refuting Jung’s definition of the term by the fact that it does not actually match the living reality. Finally, Assagioli confirms my belief that the animus, according to Jung’s definition, does not apply to women.

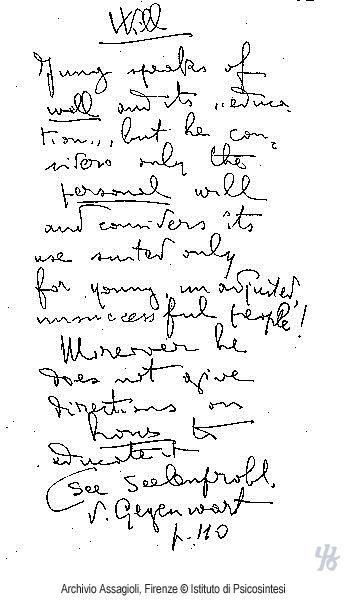

Jung Undervalued the Will

According to his biographer Deirdre Bair, Jung used his anima to avoid taking responsibility for his adulterous behavior with former client Toni Wolff. Years later, he is quoted as saying: “Back then I was in the midst of the anima problem.”

Often he felt caught in an affair that was outside of his control, saying: “What could you expect from me? – the Anima bit me on the forehead and would not let go.” This brings us to my final point regarding Jung, which Assagioli collaborates – the absence of the will from Jung’s approach (not to mention his numerous extramarital affairs!)

As demonstrated with his own confession of being dominated by his anima, Jung did not fully believe in free will. He also did not believe in determinism, but rather something in between the two. From Jung’s perspective, we are all capable of making conscious decisions, but, we are not capable of making any decision without some influence from both the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

Despite his vast number of publications, Jung wrote very little about the will. In Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, he actually warns against training one’s will, saying that the more an individual trains his will, the more danger he has of “getting lost … and deviating further and further from the laws and roots of his being”.

He wrote that the use of the personal will is only suited for young, unadjusted, unsuccessful people (!) and that a person in “the second half of life no longer needs to educate his conscious will,” but instead needs “to understand the meaning of his individual life, needs to experience his own inner being.”

All this is, of course, in sharp contrast to psychosynthesis, in which the will is given a pre-eminent position. Assagioli states that

“The will has a directive and regulatory function, one that balances and constructively utilizes all the other activities and energies of the human being without repressing any of them.”

Not only does psychosynthesis recognize that the will exists and that we have a will – but it extends even further to the fact that we are will. In his book The Act of Will, Assagioli analyses “willing action” in its various stages, describes the specific aspects and qualities of the will, and offers practical techniques for its development and optimum use (which he does not say to stop upon reaching middle age!). He regards the will as a direct expression of the “I”, the individual’s authentic being, and states:

The discovery of the will in oneself, and even more the realization that the self and the will are intimately connected, may come as a real revelation which can change, often radically, a man’s self-awareness and his whole attitude toward himself, other people, and the world.

In his historical survey of the will, Assagioli criticizes Jung’s omission:

While he recognized and even emphasized the reality and the dynamic function of goals, aims, and purposes, he did not make an investigation of the various aspects and stages of the will, nor did he include the use of the will in his therapeutic procedures.

Click here to read the full article “Psychosynthesis and Jung in a Nutshell“.

Click here to read a series on Jung and Assagioli being published by the Psychosynthesis Trust.

References

Assagioli, R. (n.d.) Archivio Assagioli – Firenze, ID Doc: 1738, 1901, 1922, 2335, 10490, 11240, 11357, 11472, 13010, 13546, 14888. Downloaded from archivioassagioli.org.

Assagioli, R. (2002). The Act of Will. London, UK: The Psychosynthesis & Education Trust.

Bair, D. (2003). Jung: A Biography. New York: Little, Brown, and Company..

Jung, C. G. (1966). The Practice of Psychotherapy (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.), Bollingen Series XX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.), Bollingen Series XX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lombard, C. A. & den Biesen, K. (2014). Reading the Divine Comedy from a psychosynthesis perspective, Psychosynthesis Quarterly, September, 2014, pp. 5-11.

Meachem, W. (2016). “Carl Jung’s Concept of Humanity and Theory of Personality,” Owlcation, October 15, 2016, https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/Psychology-405-Theory-of-Personality-The-Balance-of-Carl-Jung.

Perera, S. B. (1981), Descent to the Goddess, Toronto, Canada: Inner City Books.

Sayers, D. L. (1955). Introduction. In Alighieri, Dante, 1955. The Divine Comedy 2: Purgatory, (translated by D.L. Sayers). London, UK: Penguin Books.

von Franz, M.-L. (1964). The Process of Individuation, in Jung, C.G (ed), Man and his Symbols. London, UK: Aldus Books Limited.

Whitmont, E.D. (1968). A Jungian’s View of Psychosynthesis, Psychosynthesis Seminar 1967/8 Series. New York: Psychosynthesis Research Foundation.